Gabriel Bella, Fat Thursday Festivity in Piazzetta, 18th century, Venice, Querini Stampalia Foundation

Presented exclusively by the New Orleans Museum of Art, A Life of Seduction: Venice in the 1700s

showcases a remarkable range of objects – costume, glass, handbags, masks, a puppet theater, and exquisite paintings by Canaletto, Guardi, Longhi and others. Renowned for its beauty and singularity, Venice played a central role in the history of Western art. In the 18th century, the city experienced a revival in the arts and was the premier destination for intellectuals and travelers. Venetians cultivated a distinctive and in influential tradition of street life, festivals, and fashion.

Guest-curated by the former director of the Civic Museums of Venice, Giandomenico Romanelli, the exhibition is organized around four themes: A City that Lives on Water, the Celebration of Power, Aristocratic Life in Town and Country, and the City as Theater.

Venice in the 1700s

The city’s canals are its most important thoroughfares, providing efficient, elegant passage, and relief from the tiny, bustling streets of its 117 islands. Opulent palaces line the city’s Grand Canal and function as the regal backdrop for the frequent, civic pageantry staged on and in view of water.

In the 18th century, the canals of Venice become an artistic subject in their own right. Appreciation for the city’s singular beauty inspired the development of a tradition of view painting, the vedute. Travelers on the Grand Tour were eager for mementos, and many pictures of all types were created for export to satisfy the demand.

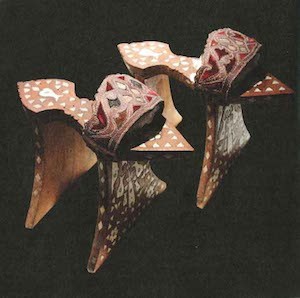

The gondola is the signature conveyance of Venice. Its unique, eminently stylish shape is designed for elegance and speed. The exhibition features two gondola models exquisitely crafted in miniature. An elaborate gondola ornament, also included in the exhibition, replicates the motifs of Egyptian Islamic metalwork, demonstrating the distinctly Venetian integration of western and eastern motifs so notable in the city’s architecture and decorative arts.

Venice was led by a tightknit group of patrician families, who each year elected a Doge as their leader. The second section of the exhibition explores the ceremony that developed around the Doge’s election process and the office itself. A painting by a follower of Joseph Heintz the Younger, Fantastic Vision of the Triumph of Venice (see gallery above), envisions a fanciful celebration of the Doge. Adapted from the traditional subject of the “triumphal entry,” the Doge is dressed in armor, riding an impossibly huge, unwieldy chariot. Flag-waving attendants celebrate him and angels sound trumpets of fame overhead. Two elephants haul the entourage, symbolizing Venice’s contacts with the exotic East.

Venice embraced luxury and masking

Venice was a center for luxury goods, including glass, furniture and textiles, all of which are featured in the exhibition’s sumptuous display of private life. A commanding, fanciful rococo desk lent by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, with its curving lines, gilt wood and delicate painted motifs is a true highlight (see gallery above). The exhibition gives special attention to fine apparel. Public and civic dress were highly regulated in the city, where strict sumptuary laws fixed appearance according to social class and gender. Black was the norm for public appearance in Venice, but in private both men and women dressed in sumptuous silks, examples of which are on display.The city boasted 17 theaters featuring opera and commedia dell’arte plays. Antonio Vivaldi worked and composed music in the city for forty years. Carlo Goldoni, at his Goldoni Theater, introduced audiences to innovative, witty productions of sophisticated complexity. His plays remain beloved by Italians. Theaters in Venice were open to all classes and the expansion of theatergoing in this period represents an important turning point in public entertainment.

By the 13th century, the wearing of masks was unique to the culture of Venice, which came to be called the “city of masks.” Masks were worn during Carnival, but Venetians often wore masks when appearing in public at other times. Seemingly a way to preserve modesty, the mask was in fact liberating. It allowed a certain anonymity and facilitated open contact and mixing between social classes and genders. The mask served to subvert a rigid social hierarchy. In 1709 city magistrates held a meeting devoted to concerns about the practice, reflecting the impact ‘masking’ had on Venetian culture. Little changed, however. As one 18th-century French tourist said, “The entire town is disguised.”

The staging of elaborate ceremonial festivities marking liturgical and political events became increasingly popular in the course of the 18th century. For example, regattas on the Grand Canal were staged to honor visiting rulers and diplomats, and great emphasis was placed on merrymaking of all sorts.

Gabriel Bella’s painting, Giovedì Grasso, depicts the celebration of the last Thursday before Lent (see gallery above). It remains a major festival in Venice, and was initiated as early as 1162. The festival centerpiece is a large, wooden tower, placed in front of the Doges’ Palace, from which reworks were launched. The painting also includes acrobats balancing on poles and o of each other, as part of the “feats of strength” competition. A wide array of other competitions were staged in squares across the city; many of them are represented in uproarious detail in paintings in the exhibition.

Vanessa Schmid, Senior Research Curator for European Art

Comments

Post a Comment