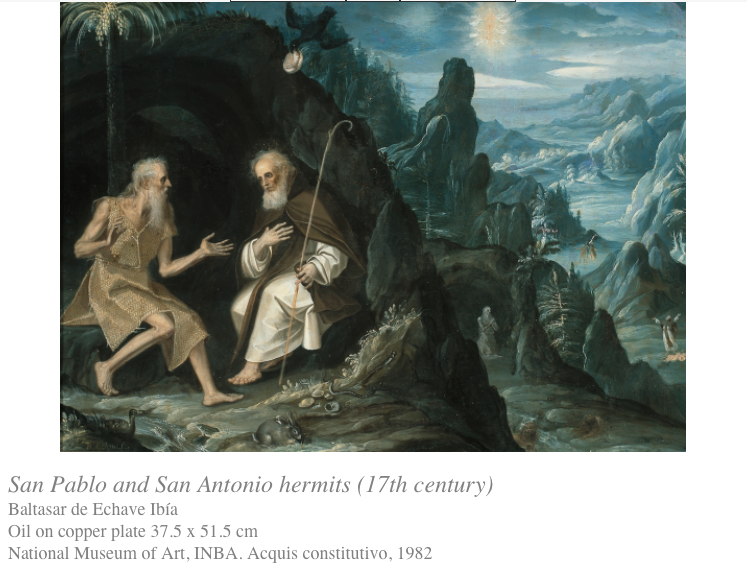

Baltazar de Echave Ibía, San Pablo y San Antonio ermitaños, siglo XVII. Museo Nacional de Arte, Inba Adjudicación, 2000.

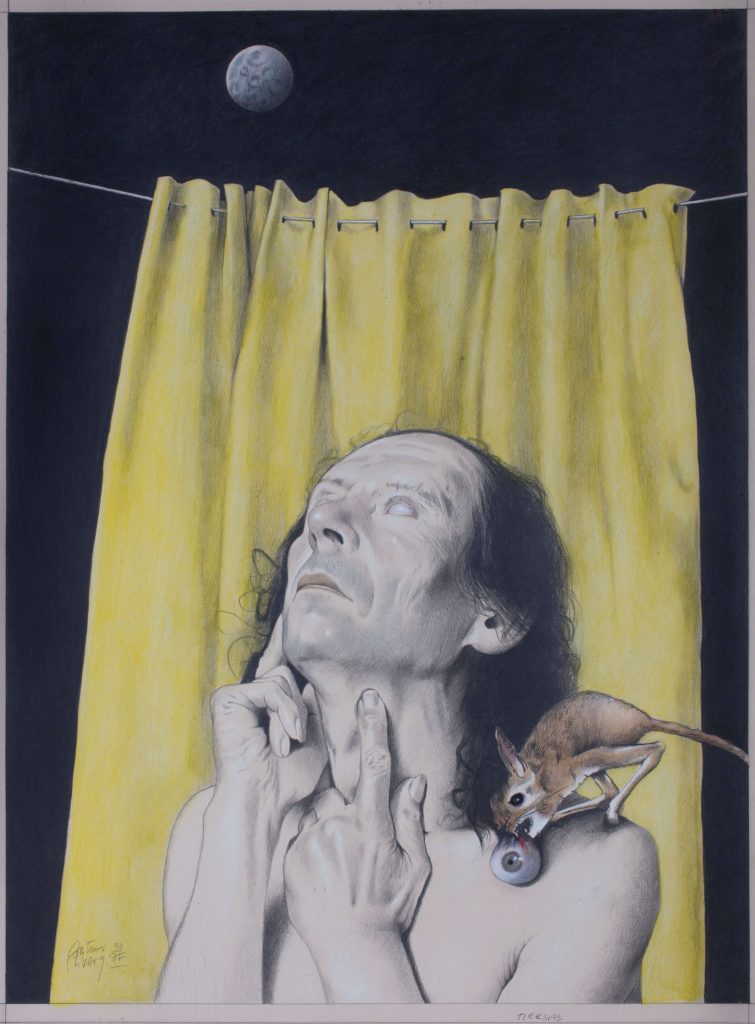

The Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL, National Art Museum of Mexico) presents ‘Melancholy’, an exhibition that delves into the manner that melancholy, commonly characterized by reflecting the darkest human sides of passion and affection, is represented in Mexican art through a selection of 137 works of art including paintings, etchings, sculptures and writings. The exhibits can be visited through April 9th of July, 2017, in the rooms on the first floor of the site.

Under the curatorship of Abraham Villavicencio Garcia, and comprised of the work of nearly 80 Mexican artists, this exposition reflects the way that human feelings are explained, interpreted and represented - revealing melancholy as a possible source for inspiration and artistic creativity.

In Villavicencio’s words, “This exhibition seeks to exalt the emotional charges evoked in the works of important novohispano, modern, and contemporary artists through themes such as sin, blame, mourning, lost love, death, spirituality, creation and magic.”

“’Melancholy’ manifests that in addition to sorrow, madness, and fear the sentiment is capable of producing creativity, heroism, intellectualism, and of the quests deep within the human psyche. To ponder upon it, through the Mexican artists’ hands that participate in this exhibition, is an opportunity to reacquaint ourselves with our age-old cultural roots that permit us to discover, under a new light, our potential for transcendence, salvation, and self-knowledge”, points out Sara Baz Sánchez, Director of the National Art Museum of Mexico.

The exhibition is comprised by four thematic nucleuses. The first theme is given the name ‘The Loss of Paradise’ where the various manners that Christianity represents bitterness and hopelessness after the fall of Adam and Eve is reflected upon, brought on by the belief of original sin and a life deprived of divine contemplation. Melancholy is seen wandering endlessly through suffering because of reproach and self-punishment. Some of the pieces that make up this section are “King of Ridicule”, 17th – 18th Century, by Cristobal de Villalpando,

and “After the Storm”, 1910, by Diego Rivera.

and “After the Storm”, 1910, by Diego Rivera.

On its behalf, ‘The Night of the Soul’ - the second nucleus of the exhibition - brings together artistic representations that refer to the lost of love such as through the death of children for mothers, widowhood, being an orphan, and love that was lost, which upon occasion lead to suicide and lifelessness. “The Empty Crib”, 1871, by Manuel Ocaranza; “Repented Margarita”, 1881, by Felipe Ocádiz; “Portrait of Sofía” ,1991, by Julio Galán; “The Lady of the Violets”, 1908, by Germán Gedovius and “Weddings from Heaven and Hell”, 1996 by Arturo Rivera are some of the works that make up this selection.

Saturn, the historic God who personifies time and identified as the most somber of the planets, was considered responsible for melancholy. Its powers gain strength in ‘The Shadow of Death’, the third nucleus of the exhibition, though which pieces like “Mary Magdalene”, c.a. 1690-1700, by Juan Tinoco; “This is the Mirror that Deceives You”, also known as “Allegory to Death”, 1856, by Tomás Mondragón; “That’s Life”, 1942, by Robert Montenegro, and “Death and Resurrection”, c.a. 20th century, by José Clemente Orozco address the reality of the world by those that bear witness to melancholy. Death becomes its greatest obsession - like a faithful dialectics and necessary for life.

Finally, ‘The Children of Saturn’ - the last of the parts of the exhibition - alludes to the idea of a renaissance by claiming that those who are born under the zodiacal sign of Sagittarius and Aquarius, regented by Saturn, are impregnated with a cosmic wisdom and artistic genius for which these individuals stand out among humanity as ascetics, prophets, saints, mystics, poets, artists, philosophers, and alchemists. They were the proof that melancholy was the pathway to ascend to the clarity of the human soul and mindfulness of the universe. Among the works that conform this section “Pierrot Doctor”, 1898, by Julio Ruelas; “Woman at the Window”, 1948, by Alfonso Michel; “The Illuminated”, 1982, by Rufino Tamayo and “Magus”, 2010, a bronze sculpture by Leonora Carrington, stand out.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment